The good God of the Balega people

A summary edited by Fr. Ferro of a research paper by Fr. Giulio Simoncelli on the culture of the Balega people and the conception of God

The Balega people live in the Kivu Region, opposite Rwanda and Burundi.

For them, but generally for the entire Bantu world, God is far away, outside and above human affairs in which, apparently, they do not care.

He is, however, the musoka, good God, who has no responsibility for the evil in the world and is never directly to blame for any bad situation that ripens among humans.

According to such a conception, God is Mun-je “He who dwells on high,” Mwene-irako “Creator and master of all,” Kinkunga “Creator,” Kalaga and Ombe “He who is from everlasting,” Mwene-byose “The Mighty One.”

His name, in the League language, is Ombe.

He is not in the least bad “Ombe ali Ombe, ali musoka wetu” (God is God, He is our good).

But no prayers are addressed directly to Him, who remains inaccessible: everything is done through intermediaries, the basumbu, the spirits of the dead in the family, and among them the closest ones such as the father, grandfather or chief-clan.

God is the custodian of the world and of mankind and acts toward them as he pleases.

Responsible for all the evil existing in the world is not God, but Akinga, “the devil,” who is the only being fully chargeable for all the evil among men: he is man’s true and only enemy and he is only evil.

Everything therefore depends on the interaction of two forces: God and the devil, who nevertheless always remains subordinate to God and is like his servant and his slave. God is always good, while the devil always wants to harm man with misfortune, disease and death. Satan, in turn, uses his “emissaries”: sorcerers, who, however, can do nothing if God does not agree.

The Balega, going back to their ancestors, remember neither words nor particular actions of God, who remains the one God, accessible only through the mediation of spirits.

One beautiful thing they saw: when one was sick and healed, they would say thus, “God wants me to stay and behold I am still alive, otherwise I would be dead.” In the case of a car accident with 8 dead, thus they say, “The sorcerers went to bewitch these men, that’s why they died. If God had been present, it would not have happened. Those men were stolen, they came out of God’s hands and heart. If God had loved those people, they would have all stayed alive.”

The Balega could have had no philosophical notion of God, but experimental notion of a God felt by instinct and of whose existence there was never the slightest doubt. They still say “Never heard that there were people who did not believe in God: everyone knew that God did only good.”

No images of either God or other spirits were ever realized.

Finally, “Where does one go after death? We knew that he who dies, rots: he is rotten where he went. He is buried, but we do not know where he goes. It is said that he goes to God and so he can intercede for us. That is where men go. It was not known that there were two ways, only one way was known: one dies and that’s it. And if the deceased helps us who are left behind, it means he is not dead yet: he intercedes where he went. So we knew that he, who is our leader, intercedes for us, his family.”

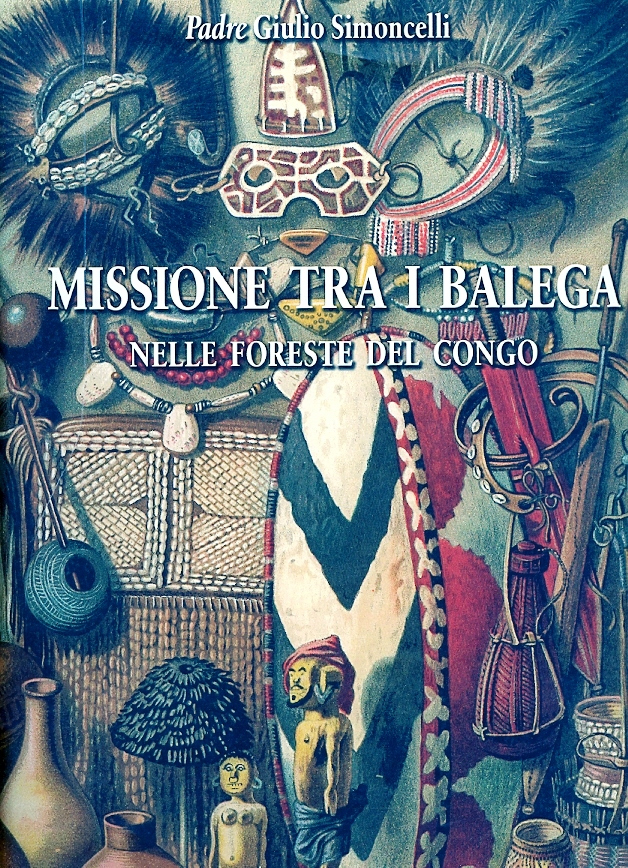

Source and image

- spazio + spadoni

- Simoncelli, G., Mission among the Balega in the forests of Congo, 2007