The Corporal Works of Mercy – Give drink to the thirsty

The Works of Mercy recommended by the Church do not have priority over one another, but all are of equal importance

One of these is “giving drink to the thirsty.” Jacopo Robusti (Venice 1518/1594) known as Tintoretto, a great Italian painter, already in his formative years as an artist, preferred to elaborate grandiose compositions, where the many characters in the various scenes, were arranged in complex architecture and scenic backgrounds. Due to his demonstrated painting skills, he was soon chosen to decorate the high school of San Rocco in Venice. One of the school’s primary tasks was to relieve the thirst of the city’s poor, and it was in the ceiling of one of those halls that he painted the scene of Moses causing water to spring from the rock in about 1577.

In the center of the scene Moses raises his staff and strikes the rock from which a strong jet of clear water gushes forth. Below thirsty people and animals throng with various vessels, drawing from that water. Moses, a man with mighty musculature a sign of his spiritual strength, looks confidently upward, where among the clouds ,with his face almost covered by his heavy clothing, God allows the miracle , but above all allows this people so fickle, despite everything, to quench their thirst. The protagonist then becomes God, who does not take guilt into account, but has mercy and grants grace to Moses who interceded and insisted with his prayers. The contrasts of light and shadows that emphasize the movements and expressions of the figures, the bright color tones and the striking background, increase the effect of tension and drama of the biblical episode. Tintoretto’s restless and tormented vision is contrasted with the calm, balanced and serene vision of another very important Italian painter.

It is entrusted to the Venetian painter Paolo Caliari (1528/1588) known as Veronese, one of the most beautiful masterpieces that narrates the well-known episode of the encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman (1585). Preserved in one of the most prestigious museums in Vienna, the work is very significant and fully expresses the fundamental concept of the Gospel passage: the conversation.

Jesus has just arrived at the well, and the flamboyantly dressed woman also seems to have arrived then. In the center is the enchantment of a fresh and lush nature in which we glimpse distant, the apostles returning bringing food. Eloquent is the gesture of Jesus who, thirsty and weary, asks the woman to give him a drink, while the woman is already about to fill her pitcher. Thus begins the dialogue between the Son of God who came to save and the person perhaps most despised by his people and consenting to their sins. Christ, with that great goodness that flows from mercy, makes her reflect on her mistaken emotional life, her difficulties, her false idols. He makes her aware of her situation and reveals to her the Truth that will change her life: “I know that the Messiah must come…. I am the Messiah.” It would seem incredible, but many Samaritans in that town believed in Him because of the woman’s word and testimony. In this painting, the sweetest expression of Christ’s face and the attentive listening of the young woman are wrapped in a delicate chromatic richness, where tonal nuances seem to emphasize the beauty of this important episode of merciful love.

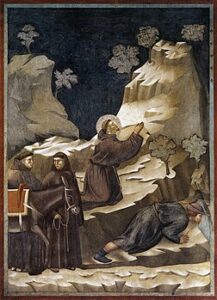

In the 1300s, painting played a very important educational role, so much so that this work of mercy was translated by Giotto di Bondone (1267/1337) a Florentine painter and architect, into the “Miracle of the Spring,” one of the twenty-eight panels frescoed for the Upper Basilica of Assisi. Having come down from the Bargello mountains, the artist first went to Assisi, accepting an apprenticeship with Cimabue. Here he not only came into contact with other talented Roman painters, but above all with the local friars, with whom he established a good relationship and gradually came to appreciate more and more the founder of the order: St. Francis. Giotto thus becomes the great storyteller who convincingly interprets what the friars are going to preach: poverty, prayer, but above all mercy. This allows us to understand why the friars of Assisi, only seventy years after the saint’s death, were able to commission from him the Basilica’s greatest pictorial cycle.

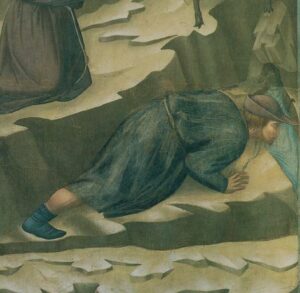

The thirsty man in the scene is not quenched directly by the saint, but is placed on the lower right because the observer’s attention must be directed to what the saint is doing: he prays! The dominant character is St. Francis who, taking pity on the strong thirst of the young man accompanying the friars, stops and, kneeling on the rocks, asks God for mercy. The scenery consists of two bare, rocky mountains and a few trees that accentuate the dryness of the terrain, making the incredible event of water suddenly gushing from the rock more evident. In the left foreground are the two friars with the donkey, looking at each other, one surprised and the other more jubilant at the miracle they are witnessing; further down on the right is the thirsty young man who, propped up on one foot, is straining only to quench his thirst, not even realizing what is taking place before his eyes.

The author in this, as in the other panels, conveys the religious message brought to the world by extolling the love for creation, the earth, water, animals, and humans through which the existence of God is recognized. Even the colors are chosen with exceptional brilliance by the master such as the large blue triangle in the sky, placed like an arrow pointing to the saint’s head. The whole scene is traversed by a contour line now thinner, now thicker that highlights not only the volumes, but enhances the physiognomy of the psychologically differentiated characters facing the miracle: serene and trusting Saint Francis, incredulous and surprised the friars, yearning for quenching his thirst the young man. The whole depiction makes us understand that the real author of the miracle here, too, is God who, in his great mercy, answers the saint’s prayer, restores the thirsty man and increases the faith of the humble friars. These great depictions should not only be admired but should lead us to reflect and act. Today it will certainly not be necessary to make water spring from the rock, but it is not difficult to perform this work of mercy toward those who extend their hand, especially from those most forgotten lands.

Paola Carmen Salamino