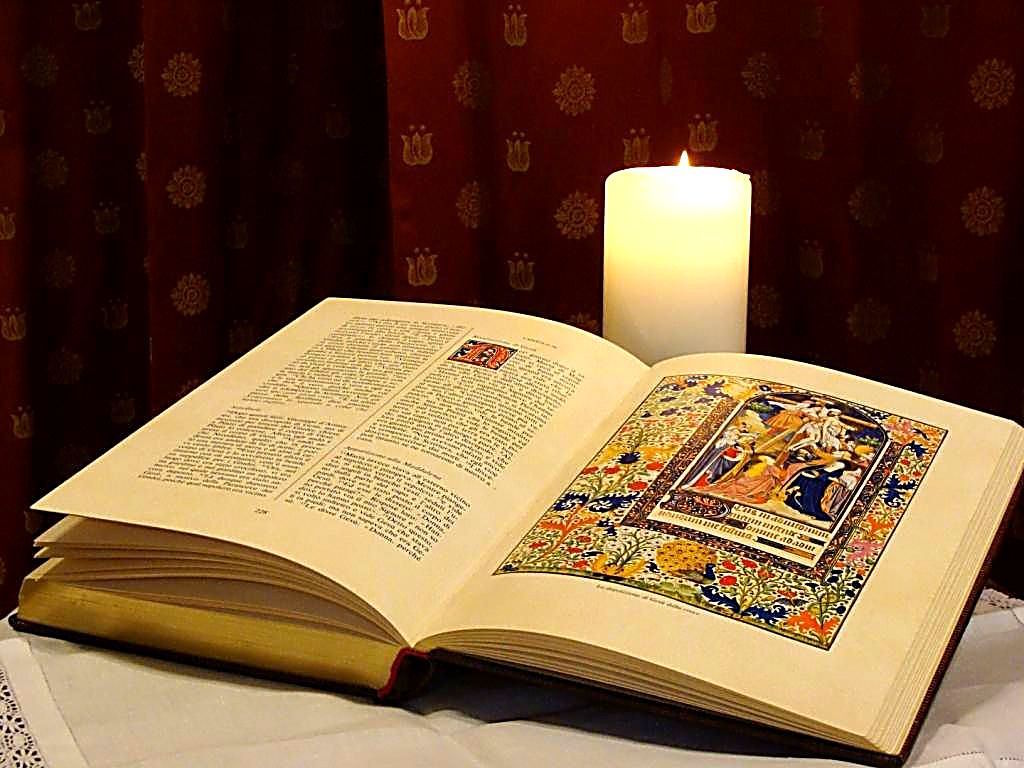

Gospel for Sunday, February 21: Mark 1: 12-15

Mark 1: 12-15

12Immediately afterwards the Spirit drove him into the desert

13and he remained there for forty days, tempted by Satan; he was with the wild beasts and the angels served him.

14After John was arrested, Jesus went to Galilee preaching the gospel of God and saying:

15“The time is fulfilled and the kingdom of God is near; convert and believe in the gospel”.Mark 1: 12-15

Dear Sisters and Brothers of the Misericordie, I am Carlo Miglietta, doctor, biblical scholar, layman, husband, father and grandfather (www.buonabibbiaatutti.it).

Also today I share with you a short meditation thought on the Gospel, with special reference to the theme of mercy.

DO NOT ABANDON TO TEMPTATION

The New Missal has finally changed the sixth of the seven invocations of that oratio perfectissima of Jesus – as Thomas Aquinas defined it – which is the Our Father, that is, “lead us not into temptation”, into “do not abandon ourselves to temptation”.

God does not tempt anyone

The previous translation might have implied that God tempted people. But this cannot be because God does not tempt anyone. He himself said it through the mouth of James: “Let no one, when he is tempted, say: «I am tempted by God»; because God cannot be tempted to evil, and he tempts no one” (Jas 1:12).

Vittorio Messori reported a distant meeting with the abbot Jean Carmignac, a great biblical scholar, who, precisely because of his profound knowledge of the linguistic background of the Gospels, said he was deeply saddened by being “forced to pronounce several times a day what he considered a ‘authentic blasphemy’, that is, the infamous ‘lead us not into temptation’. And, “based on the Semitic original hidden under the Greek text, he proposed as truly faithful to the words of Jesus a «do not allow us to succumb to temptation (of the Evil One) »”. “His insistence and his patience – concluded Messori – were rewarded, even after his death”. Even though he believed that the old biblical scholar would not be completely satisfied with the new official translation (“do not abandon us to temptation”), he certainly considered it consoling that “no Christian, pronouncing his dearest prayer, will have to fear blaspheming rather than than to pray.”

The Aramaic background

The new translation of the Missal dates back to the Greek original which, however, certainly has an Aramaic undertone, the language used by Jesus, in which the verb used probably had a permissive value: “Do not leave us/do not let us enter into temptation”. “Induce” in Italian has become overloaded with a volitional connotation (to introduce, push in) which no longer makes it mean the same thing as the Latin inducere or the Greek eisferein, where a concessive sense was implicit (don’t let in, let that we do not enter)”: it literally indicates “not taking us towards”, different from “inducing” which is “pushing” someone concretely to carry out an action. As the CEI Document presenting the New Missal says, “the genuine meaning is, then, that of not being exposed and abandoned to the risk of temptation. The choice is justified by the fact that the connotation of the Italian “induce” expresses a positive will while the original Greek eisferein rather contains a concessive nuance (do not let us in). The new translation expresses at the same time the request to be preserved from temptation and to be helped if temptation occurs.”

Don’t abandon us to temptation

Without God’s help we cannot overcome trials. Thomas Aquinas states: “For this reason we say with the Psalmist: «Do not abandon me when my strength declines» (Ps 70,9). God supports man, so that he does not fall into temptation, through the fervor of charity which, however little it may be, is sufficient to preserve us from any sin. In fact “much waters cannot quench love” (Song 8:7)” (Commentary on the Pater).

TEMPTATION: TRIAL OR PITFALL?

“At this point, however, it is necessary to distinguish between «temptation-test» and «temptation-snare», both possible meanings in the Greek peirasmós used by Matthew. The test can have as its subject God who evaluates the faithfulness and purity of man’s faith: think of Abraham, invited to sacrifice Isaac, the son of the divine promise (Gen 22), of Job, of Israel harshly “corrected” by God in the desert “as a man disciplines his son” (Dt 8,5). It is an education in loyalty, in disinterested donation, in pure love without double ends. A phrase from the First Letter to the Corinthians of St. is consoling in this regard. Paul: «No temptation greater than human strength has surprised you; In fact, God is worthy of faith and will not allow you to be tempted beyond your strength but, together with the temptation, he will also give you the way to escape from it in order to be able to withstand it »” (10,13).

The “snare temptation” is different, which aims at man’s rebellion against God and his law and which, at first sight, should have Satan or the sinful world as its root… Moral evil must be traced back either to freedom human or to the tempter par excellence, Satan.

In this regard, the seventh and final question is also important, which is the positive version of the previous one: “Deliver us from evil!”. It is interesting to note that in the original Greek one can imagine in the wordponeroù both the translation “from evil” and “from the Evil One”, i.e. the devil, and both meanings are acceptable and can coexist. During the Last Supper, Jesus offers Peter a suggestive representation of divine help to “free us from evil/Evil”: “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan has sought you to sift you like wheat. But I have prayed for you, so that your faith may not fail” (Lk 22,31-32).

A well-known French Orthodox theologian, Olivier Clément, noted: «The Our Father is not concluded by praise or thanksgiving, but remains suspended in a pressing cry of misery», while man feels himself on the edge of the dark abyss of pain and of evil. This is why some ancient codes, followed by tradition and Protestant worship, felt the need to add this acclamation at the end to the Our Father: “Yours is the Kingdom, the power and the glory forever!”.

But, with her usual finesse and her sensitivity for the Christian message, despite its Jewish origin, Simone Weil in her work «Waiting for God» (1950) acutely observed that the path of the Our Father is antithetical to that which usually governs every prayer that goes from bottom to top, from man and his misery to God and his light. Here, however, he starts from the sky and descends into the dark tangle of evil” (G. Ravasi). Jesus, succumbing to temptation like all men, but always remaining faithful to the Father in it, becomes the perfect Man who, the Evangelist tells us, is with the wild beasts and the Angels, like Adam in Paradise.

Happy Mercy to all!

Anyone who would like to read a more complete exegesis of the text, or some insights, please ask me at migliettacarlo@gmail.com.