Gospel for Friday, December 25: Luke 2: 1-14

Lord’s Christmas

1In those days a decree by Caesar Augustus ordered that a census be taken of the entire land. 2This first census was taken when Quirinius was governor of Syria. 3Everyone was going to get a census, each in their own town. 4Joseph, too, went up from Galilee, from the city of Nazareth, to Judea to the city of David called Bethlehem: for he belonged to the house and family of David. 5He was to be enumerated together with Mary, his bride, who was pregnant. 6While they were in that place, the days of childbirth were fulfilled for her. 7She gave birth to her firstborn son, wrapped him in swaddling clothes and placed him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the lodging. 8There were some shepherds in that region who, sleeping in the open, kept vigil all night by guarding their flocks. 9An angel of the Lord came to them, and the glory of the Lord enveloped them with light. They were seized with great fear, 10But the angel said to them: “Fear not: behold, I announce to you great joy, which shall be to all the people: 11Today, in the city of David, a Savior has been born to you, who is Christ the Lord. 12This is the sign for you: you will find a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.” 13And immediately there appeared with the angel a multitude of the heavenly army, praising God and saying: 14“Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men, whom he loves.”

Luke 2: 1-14

Dear Sisters and Brothers of the Misericordie, I am Carlo Miglietta, doctor, biblical scholar, layman, husband, father and grandfather (www.buonabibbiaatutti.it).

Also today I share with you a short meditation thought on the Gospel, with special reference to the theme of mercy.

A strange census

“Luke places the birth of Jesus in the setting of Bethlehem, a town near Jerusalem, homeland of King David, on the occasion of a census ordered by the “governor of Syria Quirinius” (read Luke 2:1-7). Pieter Bruegel the Elder in a canvas from the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels (1566) delightfully depicted the flocking of a dense crowd of merchants, farmers and beggars to Bethlehem, immersed in the snow, to be registered according to a census conducted at roots, that is, to the homes of origin of the families, a practice attested in Roman Egypt, even if the residential census was predominant.

There is, however, a rather serious historical difficulty. The only documented census of Quirinius in Palestine was carried out in 6-7 AD, when Jesus was at least twelve years old and amazed the doctors of the law in the temple of Jerusalem (Lk 2,41-52). As is known, the chronological calculation of the birth of Christ is almost certainly erroneous due to the imprecise calculation of the monk Dionysius the Little of the 6th century, who set the event in the year 753 from the foundation of Rome. In fact, the Gospels state that Jesus was born under Herod the Great who died around 4 BC.

In evoking that census operation, did Luca perhaps confuse the dates? Or did he do it to give the birth of Jesus a universal dimension? We know that the Gospels, although they narrate the historical story of a concrete figure like Jesus of Nazareth, do not have rigorous historiographical concerns. However, we also know that Luke is the evangelist who is most attentive to historical data. It is therefore possible to follow two paths.

On the one hand, it can be stated – as an important commentator on Luke, Heinz Schürmann writes – that “the theme of the census places the birth of Jesus in relation to the entire empire. In him not only is the expectation of the Jews fulfilled but of the whole earth. A horizon as vast as the world opens up; the universal importance of the birth of Jesus is affirmed.” The question should therefore be addressed on a theological and symbolic level, certainly not historiographical. As another German scholar, Emil Schürer, writes in his History of the Jewish People at the Time of Jesus, a classic work of the 19th century, “Luke would have generalized into a single event the various censuses ordered by Augustus in different times and places”, so as to place the birth of Christ within a universal and planetary scope.

On the other hand, however, one can attempt to sift through all the available historical data, as various scholars have done in different forms. For example, according to the historian Giulio Firpo, in his 1983 study on the chronological problem of the birth of Jesus, “the first census”, as Luke defines it (Lk 2,2), should be framed in a global census plan designed by Augustus, destined to also involve an autonomous and exempt kingdom, such as that of Herod, rex socius et amicus, that is, king allied and friend of Rome. In 7-6 BC, therefore, an administrative census was carried out in Palestine, connected to an oath of loyalty to the empire and conducted according to the tribal and non-residential method for reasons of tactics and political caution. It was managed by Quirinius, at that time regent with special assignment of the Syrian legation, ordinarily held by the governor Sanzio Saturnino, then engaged in a harsh war against the Armenians. This would be the census during which Jesus was born. When he becomes fully responsible for Syria, Quirinius will order the second census, better known and documented, that of 6-7 AD. What is certain is that, beyond historical questions – there is even some scholar who tries to confirm the current dating of the Christian centuries – Luke sees in the birth of Christ an event with universal echoes and an impact on human historical events.

The emperor Augustus announced a census for his entire empire, by virtue of which every citizen subjected to Rome had to go to his hometown to register: the purpose was based on taxation. Faced with an emperor who believes himself to be powerful because he counts his subjects by setting an empire in motion, there is an obscure family from Galilee who keeps the secret of a birth announcement and sets off from Galilee to Judea. Everything seems to happen by chance, but nothing is random. Men struggle to manage their little history, believing themselves to be «great»: they are only the occasion of processes that escape their consideration because the new history must start again from the «city of David»” (G. Ravasi).

The contrast of values

“In the 2nd chapter of the Gospel of Luke, the contrast effect dominates which highlights what happens this night and establishes what is important and what is appearance. This leads us to review what our evaluation criteria are, the discernment of the facts we experience. In front of the emperor Caesar Augustus stands a Jewish girl named Miriam. She is the powerful one and a little girl.

The emperor rules the world, the girl is alone and is only pregnant.

On the one hand, the emperor announces a census as a sign of power: to count his subjects to impose taxes; on the other hand, the dark Jewish girl is in a deep relationship with someone Else to whom she leaves the counting of the days of her give birth. The powerful man believes he governs the world and events, while the Jewish girl is content to become aware that “the days of childbirth have come for her” (v. 6) and dedicates herself to the birth of her son. The powerful think they govern the entire world, the Jewish teenager only gives birth to Life. The emperor moves millions of people with a single order, forcing them to obey him. For her part, Mary sets herself on a journey to serve her cousin Elizabeth who she has to give birth to: power and service. The powerful man remains still in his palace, the Jewish woman starts moving.

The emperor is served and obeyed, the woman serves and abandons herself to the will of her Creator (Lk 1.38).

Faced with an emperor whom she orders, Mary realizes herself in the will of an Other: «Oh, yes! May it happen in me according to your Word” (Lk 1,38) and in her the “Word was made flesh” (Jn 1,18). The same Word that tonight becomes Bread to nourish our thirst for life and love: even the town where Jesus is born is a prophetic announcement: Bethlehem in Hebrew means House of Bread” (P. Farinella).

The birth of Jesus

In the Gospel of Luke, while the birth of John is narrated in two verses (Lk 1.57-58), twenty verses are dedicated to that of Jesus (Lk 1.1-20). There can be no greater contrast than that described for the birth of Jesus. Even in comparison with John the Baptist, everything is upside down:

1. the announcement of the birth of John takes place in the sumptuousness of the Temple, the announcement of the birth of Jesus takes place in Nazareth in the region of Galilee equated to the pagan nations and contemptuously called: “Galilee of the Gentiles” (Mt 4.15);

2. John is born in his house, Jesus is an emigrant and was born traveling along the road;

3. the birth of John attracts relatives and neighbors, the birth of Jesus only the shepherds, legally impure and socially marginalized. The whole life of Jesus is a contrast and a reversal that shows us how the God of Jesus comes in an unexpected way and outside of every scheme and preconception.

In this story Luke summarizes the message of the entire Gospel:

the true humanity of Jesus: “This is a sign for you: you will find a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger” (Lk 2:12). Luke uses “crude” terms: “brèphos” (Lk 2,12.16), which indicates the fetus to be given birth or just given birth, and “gennòmenon” (Lk 1,35), which designates the fetus in the mother’s womb;

the divinity of Jesus: the announcement to the shepherds (Lk 2.9-13) is a true Easter announcement, as we have seen

the choice of the poor: Jesus was born with the poor of his time, “laid in a manger because there was no room for them in the <>” (Lk 2.7), that is, the part of the cave where Joseph’s family stayed , used as a shelter for men and not for animals (same term used for the room of the last supper; but it does not in itself speak of birth in a cave or in a stable). His birth is announced not to the great or the wise, but to the “impure”, such as the shepherds, who become the first disciples:

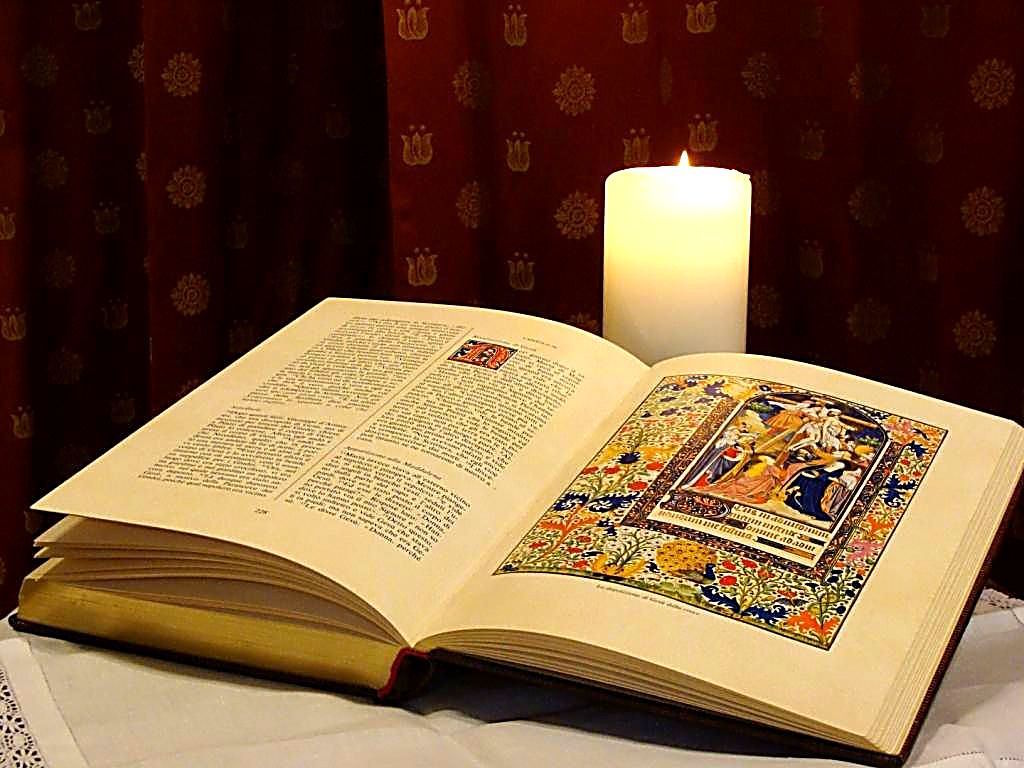

Christmas in Luke is immediately connected to Easter: Mary “wrapped Jesus in swaddling clothes and placed him in a manger” (Lk 2.7), just as Joseph of Arimathea “wrapped him in a cloth and laid him in a tomb” (Lk 23.53 ) the body of the crucified, and these “bandages will lie empty” (Lk 24,12); in Bethlehem the “impure” shepherds are the first witnesses of the birth of Jesus (Lk 2,8-20), in Jerusalem they will be the ” impure” women the first witnesses of his resurrection (Lk 23.55-24.10); in both events, there are angels to give meaning to the mystery (Lk 2.9-14; 24.4-7). In the little Jesus – according to the orientation of the Infancy Gospels – we can already glimpse the glorious risen “Lord”, proclaimed by the Paschal faith of the Church. The typology of the Russian icon of the Novgorod school (15th century) makes this connection explicit by depicting the baby Jesus wrapped in swaddling clothes and placed in a manger that has the shape of a tomb” (Ravasi).

The annunciation to the shepherds

“There were in that region some shepherds who kept watch at night guarding their flock”: these are the presences that populate the desert of Judah adjacent to Bethlehem… In the treatise Sanhedrin (25b) of the Talmud, the great collection of Jewish traditions , we read that the shepherds could not testify in the trial because they were considered impure, due to their coexistence with animals, and dishonest, due to their violations of territorial boundaries. Their civil status was, therefore, at the bottom of the social ladder and their living conditions were much less “georgic” and idyllic than Virgil or Theocritus have accustomed us to think.

Christian tradition placed their camp for that night in the current Arab village of Bet-Sahur, three kilometers from Bethlehem, in a location called “Shepherds’ Camp”, occupied in the 4th-6th century by a Byzantine monastery built on caves used by shepherds for their night vigils. Now there stands a modern church (1953) which aims to imitate the Bedouin tent in its structure and whose dome lets the light of the sky filter through almost in a play of stars.

After the annunciations to Mary and Joseph we can then speak of an annunciation to the shepherds. Also in this case the angels are on stage singing that “Gloria in excelsis” which will be sung in thousands and thousands of Masses over the centuries. This chorus that comes from the lips of “the whole heavenly host”, as Luke biblically calls the angels, will be relaunched from earth to heaven when Jesus enters Jerusalem for the last week of his life. On the night of Christmas the angels had sung: “Glory to God in the highest heaven and peace on earth among men (object) of (divine) good will” (this is the most correct version of Luke 2.14, where it is the love of God and not so much human will). On the threshold of the Passion, during the entry into Jerusalem, the disciples will sing: “Peace in heaven and glory in the highest heaven!” (Luke 19:38). Raymond Brown comments in an important work on The Birth of the Messiah according to Matthew and Luke: “It is a fascinating touch that the multitude of the heavenly militia proclaims peace on earth, while the multitude of disciples proclaims peace in heaven: the two passages could almost become an antiphonal responsory”.

However, in the midst of the choreography of the angelic epiphany there is a specific message, addressed to the shepherds. In the original Greek Luke defines it as a “gospel” and it has an exquisitely theological content: “Today there has been born for you in the city of David a savior, who is Christ the Lord” (Lk 2:11). It is a small Christian “Creed” that revolves around three fundamental titles attributed to the Child: Savior, Christ (i.e. Messiah), Lord (i.e. God). Paul also knows this Creed and quotes it when writing to the Christians of Philippi: “We await the Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ” (3,20).

Well, the first to come on pilgrimage to Christ the Lord are the last on earth, anticipating a saying dear to Jesus: “The first will be last and the last first” (Mt 20.16). The entire Lucanian story is dotted with verbs of motion and surprise: “let’s go, we know, they went, they found, they saw, they reported, everyone heard, they were amazed, they returned glorifying and praising God for everything they had heard and seen”. The family of Bethlehem is surrounded by shepherds, those rejected by the Sanhedrin, the marginal ones who Luke, however, sees as the prefiguration of the Church of Christ” (G. Ravasi).

Happy Mercy to all!

Anyone who would like to read a more complete exegesis of the text, or some insights, please ask me at migliettacarlo@gmail.com.