Fr. Ferdinando Colombo: Visiting Prisoners

Actualizing the works of mercy through the eyes of Fr. Ferdinando Colombo

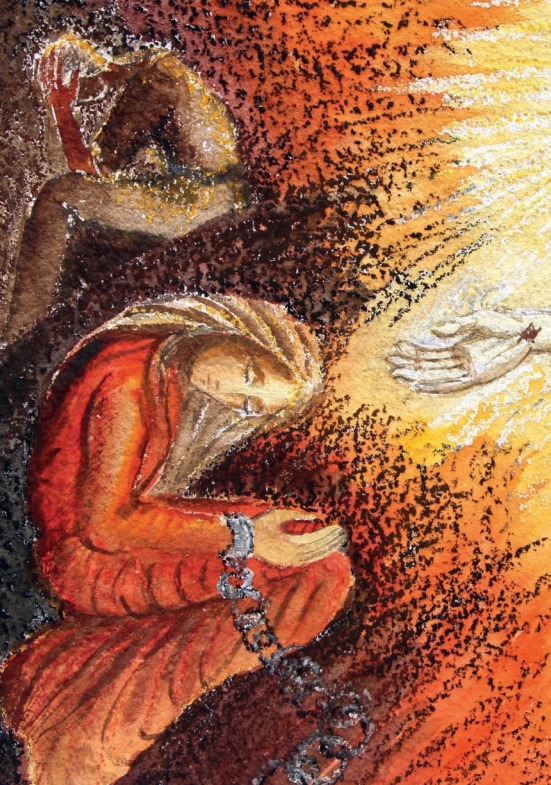

If the story of man’s violence, an evil so deep, so real, starts from Cain and ends on the Cross; to triumph there is nothing but God’s death. And if Jesus dies, he chooses to do so between two criminals. One comes out divinely, going from defeat to absolute victory, first saved by Christ’s death. The other will persist in his rejection of the offered grace. To understand the work of mercy toward prisoners, we must start from that teaching of Jesus when he tells of the prayer of the publican and the Pharisee (Lk.18:9-14).

Once there were two men: one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector. One day they went up to the Temple to pray. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus to himself, “O God, I thank you that I am not like other men: thieves, cheaters, adùlters. I am different even from that tax collector. I fast twice a week and offer to the Temple the tenth part of what I earn.”

The tax agent, on the other hand, stood back and would not even look up. In fact he beat his chest saying, “O God, have mercy on me who am a poor sinner!” I assure you that the tax collector went home forgiven; the other did not. For, he who exalts himself will be brought low; he who lowers himself will be lifted up.

The parable begins by highlighting the fact that “being righteous” is never a native condition of the human person; in fact, the Christian is never righteous before God. The overconfidence of one’s innocence, especially when it has as its practical implication a judgmental and intolerant attitude toward one’s neighbor and his or her mistakes, is something that should make one think. The Christian is not configured as a “righteous” man, but as a man reconciled, forgiven, justified by God. That is why this parable shows this “picture” between two models: the man who defends his personal righteousness, which God does not validate, and the man who surrenders before God’s mercy and is justified.

The case: Story of Jacques Fesch

The prison world is, by its very nature, grim; and yet evil, both physical and moral, can become the occasion for a serious rethinking of life. This has been the case for many. I think of the story of Jacques Fesch, a young thief and murderer of our times, born in 1930 and ending up on the guillotine on October 1, 1957, for killing a police officer in Paris. Jaques, in solitary confinement, was able to take a long examination of his life and little by little rediscovered his faith. He read a lot, especially the Gospels, until he came across the young Carmelite Therèse de Lisieux, who was his spiritual guide until the day of his execution. He wrote very tender letters to his companion Pierrette, by whom he had a daughter, Veronique, and whom he married a few days before his death. During the years of his trial he had the opportunity to meet Christ, who in the solitude of the cell could speak perhaps more clearly than elsewhere: “You too have been taken there where you would not have wanted to go,” he wrote in his diary, thinking of Jesus. At the feet of the Crucified One he learned, as he wrote, “to accept the cross, which little by little will become light; to offer one’s suffering and the injustices of which one is the victim; to love those who lash us. And so one day I will hear myself say like the good thief crucified, ‘Truly I say to you, this very day you will be with me in paradise. “Grace has visited me,” he concluded, ”and a great joy has taken hold of me, and above all a great peace…. This is the first time I cry tears of joy, having the certainty that God has forgiven me.” On the last night of her life, the night between Sept. 30 and Oct. 1, 1957, she wrote her baby a most moving letter “for when she is a woman”: “You are so beautiful, Veronique!” Then came her earthly end, welcomed with peace: “Last day of struggle: tomorrow at this time I will be in heaven! I trust in the love of Jesus and know that he will commission his angels to take me on their hands.” The guillotine that severed his head actually freed him as one frees a butterfly from its chrysalis. Now there is even talk of a beatification process for him. With God, one can even turn the solitary confinement cell into a small church, a misguided existence into a path of holiness, a guillotine blade into a halo of light!

The Witness: Don Giuseppe Cafasso (1811-1860)

Don Bosco’s confessor, Don Cafasso devoted himself to the least and to the imprisoned. Pope Benedict said of him, “He knew moral theology, but he knew equally well the situations and hearts of the people, whose good he took upon himself, like the Good Shepherd. Those who had the grace to be near him were transformed by it into as many good shepherds and good confessors. He clearly indicated to all priests the holiness to be attained precisely in pastoral ministry.” He was a frequent visitor to the Senatorial prisons, so much so that he stayed there until late at night, sometimes all night. He brought cigars and snuff, instead of the lime that the inmates scraped from the walls; but above all he brought thieves and heinous murderers to conversion. They were slow and tormented repentances; at other times, however, they were immediate conversions, occurring even moments before hanging. Pope Benedict XVI again said of him, “From his chair of moral theology he educated to be good confessors and spiritual directors, concerned for the true spiritual good of the person, animated by great balance in making people feel God’s mercy and, at the same time, a keen and vivid sense of sin.”

Brothers, sisters of the prison: the jubilee, which makes us encounter a Father who forgives and consoles, can work miracles for everyone and with everyone. “Even the time spent in prison,” the Pope writes, ”is God’s time and should be lived as such. It is a time that must be offered to God as an occasion of truth, of humility, of atonement, of faith. The Jubilee experience, even if in prison, can lead to unhoped-for human and spiritual horizons.” (Cardinal Gualtiero Bassetti, Archbishop Emeritus of Perugia)

PRAYER of Paul VI

You are necessary to us, O our Redeemer, to discover our misery and to heal it;

to have the concept of good and evil and the hope of holiness; to deplore our sins,

especially when the victims are children, and to have their forgiveness.

You are necessary to us, O great patient of our sorrows,

to know the meaning of suffering, exploitation, violence, and to give it a value of atonement and redemption.

You are needed by us, O Christ, O Lord, O God with us,

to walk in the joy and strength of your charity, until the final encounter with you beloved, with you awaited,

with you blessed for ever and ever. Amen

Online version of the book by clicking on “The Work of Mercy – Fr. Ferdinando Colombo – browsable”

Photo

- “Le Opere di Misericordia“, fr. Ferdinando Colombo