Fr. Ferdinando Colombo: Enduring Harassing People

Actualizing the works of mercy through the eyes of Fr. Ferdinando Colombo

A famous text from the Christian tradition, Franciscan in particular, allows us to introduce this work of mercy in a critical and problematic way.

In the Fioretti, Francis explains to Brother Leo what perfect gladness consists in and tells him:

“When we shall be at Santa Maria degli Agnoli, so wet from the rain and chilled from the cold and muddied with lotus and afflicted with hunger, and we shall beat the door of the place, and ‘the porter will come angry and say, Who are you?

And we will say, We are two of your brothers; and he will say: You do not speak the truth, rather you are two rogues who go about deceiving the world and stealing the limosine of the poor; go away; and he will not open to us, and make us stand outside in the snow and water, with cold and hunger until night; then if we so much injustice and so much cruelty and so many commendations shall patiently endure without being troubled and without murmuring of him, and humbly think that that porter truly knows us, that God makes him speak against us; O Friar Lyon, inscribe that here is perfect gladness. And if indeed we persevere in beating, and he will come out disturbed, and like importunate scoundrels he will drive us out with rudeness and with gotate, saying, Depart thither, most vile rogues, go to the dispensary, for here you will not eat, nor will you lodge; if we will patiently and cheerfully and with good love sustain this; O Friar Lyon, inscribe that here is perfect gladness.

And if we though constrained by hunger and cold and night the more we shall beat and call and pray for the love of God with great weeping that he would open us and put us in, and those most scandalized shall say, These are importunate scoundrels, I will pay them well as they are worthy; and he shall come out with a helmeted stick, and seize us by the hood and gitter us on the ground and wrap us in snow and beat us knot by knot with that stick: if we will bear all these things patiently and cheerfully, thinking the pains of the blessed Christ, which we must bear for his sake; O Brother Lyon, inscribe that here and in this is perfect gladness.”

The text questions us: who is “annoying” in this story? The two friars who knock insistently seeking shelter from the cold and the night? Or who doesn’t want to welcome them by giving pretexts and not listening to reasons? That is: when is a person perceived as harassing? When, and why, does it bother us? When do we feel that a person is unbearable? Why does a certain person’s behavior bother us?

In perceiving annoyance in front of someone and in feeling their unbearability there is also a revelation of us to ourselves. In feeling a person as annoying and annoying there may simply be the expression of selfish and racist feelings or of fear and refusal of confrontation. One can think, for example, of the feeling that many feel towards immigrants who arrive in our country.

Furthermore, this text presents a sensational case of refusal of patience and tolerance towards those who are perceived as annoying, but also a heroic case of tolerance and patience towards the unbearability of others transformed into aggressive violence.

This endurance is founded on the gospel and the example of Christ and made possible by faith. In fact, Francis continues his speech to Brother Leo by stating that the grace of the Holy Spirit is to be able to conquer oneself and willingly for the love of Christ bear punishments, insults and opprobriums and inconveniences, without boasting of this, but placing one’s boast solely in the cross of Christ: “In the cross of tribulation and affliction we can glory, because the Apostle says: I will not glory except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ (Gal 6:14)”.

Patience is God’s great gaze towards man, a gaze that does not stop at the detail, at the accident, does not consider sin as final, but places it within the entire existential journey that man he is called to travel. Therefore it exposes God to the risk of not being taken seriously, of being “used” by man. In Christ, and particularly in his passion and death, God’s patience reaches its peak as a radical assumption of man’s inadequacy and weakness, of his sin.

In Christ, God agrees to “carry the burden”, to “endure” human incompleteness and inadequacy by assuming responsibility for man in his fallibility. The “patience of Christ” (2Th 3.5) thus expresses the love of God and is its sacrament.

Today, however, patience has lost a lot of its charm: hasty times lead to impatience, to non-deferral, to “everything now”, to possession that leaves no room for waiting.

The individualistic self-affirmation becomes an unwillingness to wait and understand the other which too quickly risks becoming annoying or annoying, certainly an obstacle. So patience, which was once a wise and human way of inhabiting the world, is now forgotten. At the same time, it is necessary to realistically recognize that patience is not always a virtue, just as impatience is by no means always a non-virtue.

Patience is an art. Which has nothing to do with passively suffering. Instead, it is those who are not patient who, much more often, suffer. Patient but free and loving tolerance towards those who are annoying, unpleasant, boring, slow, is in line with the love of the enemy (cf. Mt 5,38-48; Lk 6,27-35). And it requires work on ourselves to learn to know and love the enemy within us, what is annoying in us, what is unbearable for ourselves and which God, in Christ, has patiently endured, loving us unconditionally. In this way patience becomes an opening to the future for the other, confirmation of trust in him, struggle together with him and for him against the temptation of desperation. (Luciano Manicardi)

Prayer

I ASKED GOD by Kirk Kilgour

I asked God to be strong to carry out grandiose plans: He made me weak to keep me in humility.

I asked God to give me the health to accomplish great feats: He gave me the pain to understand it better.

I asked him for wealth to possess everything: He made me poor so as not to be selfish.

I asked him for power so that men needed me: He gave me humiliation so that I needed them.

I asked God for everything to enjoy life:

He left my life so I could appreciate everything. Sir, I didn’t get anything I asked for,

but you gave me everything I needed and almost against my will.

The prayers I didn’t pray were answered. Be praised; oh my Lord,

among all men no one has what I have!”

Online version of the book by clicking on “The Work of Mercy – Fr. Ferdinando Colombo – browsable”

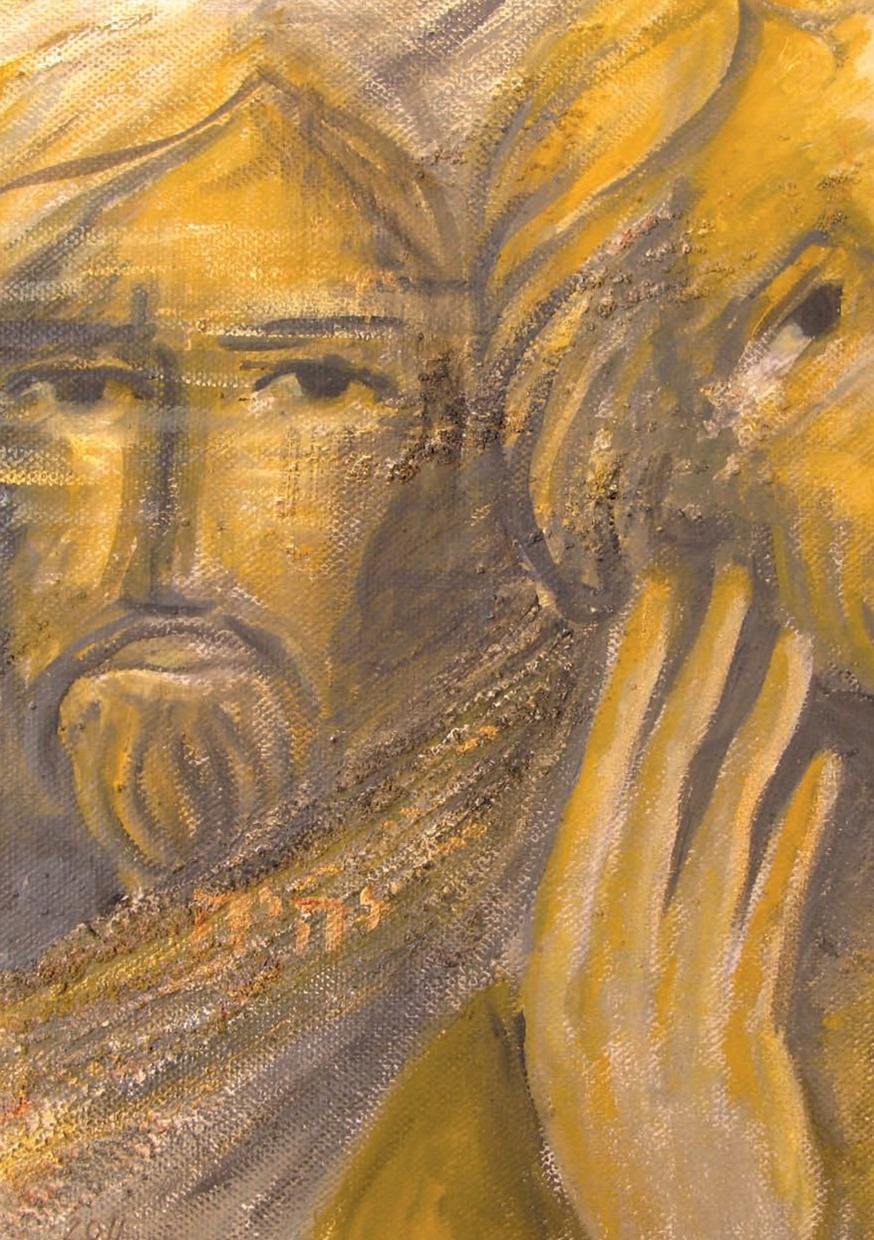

Photo

- “Le Opere di Misericordia“, fr. Ferdinando Colombo