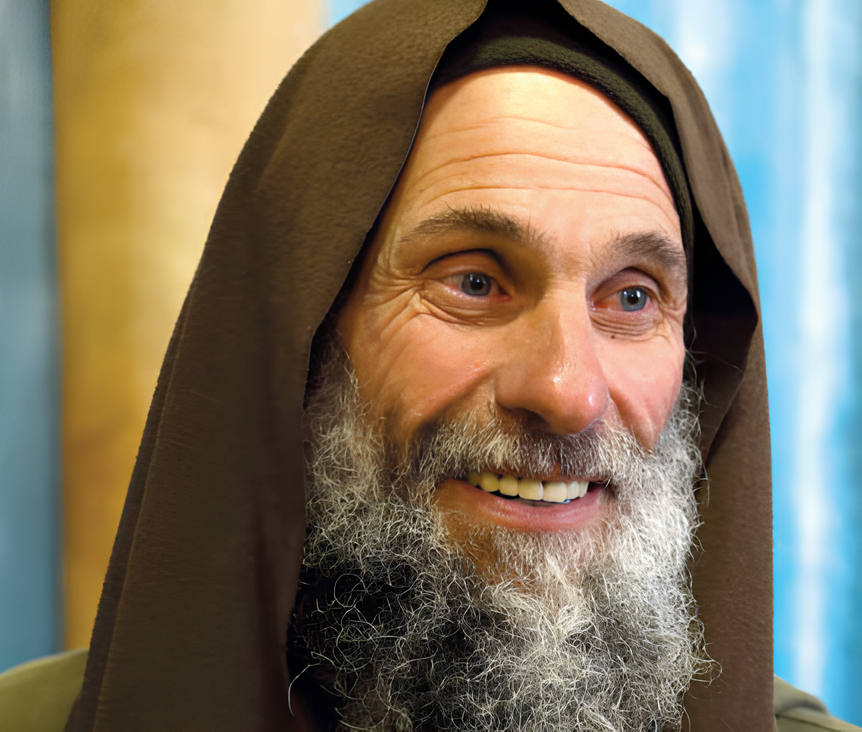

Biagio’s legacy: everything for the poor

Retrace the life of Brother Biagio Conte, to nurture his works of mercy and his words, “Take care of the poor”

There are exactly 950 meters between Palermo Central Station and Via Archirafi. Roughly 10 minutes on foot, at a brisk pace, via Corso dei Mille. But there is a more subjective distance between us and the poor, and it can be a longer or shorter, sometimes winding or never beaten path.

Biagio Conte, on the other hand, has made it his high road since he began providing relief and comfort to the homeless in 1991.

“Choosing the most appropriate places was crucial for him,” Don Pino Vitrano, who has always been at his side, tells us. “So many brothers gravitate to the station and their issues are triggered by the concept of departure. The station, then, as a “pole of gathering, sharing and life,” as “the heart that waits to be sought in the moment of trial.”

“May I call you brother?” was his most recurring question. The key that opened the closed doors in a world of desperate people and made each person feel precious,” the Salesian continues as outside there is the typical bustle of families in the morning, with beds and existences to be made over.

It is a bustle of guests, volunteers, staff and visitors. As Brother Claudio Parotti, a Comboni missionary for 12 years in Colombia, recalls, “there, borders are very relative. It struck me to see several hundred people and not be able to draw a border.”

This was also the case at his funeral, with more than 10,000 people from various backgrounds. “The participation of the Jewish community, Catholics, Muslims, Hindus and even many atheists is the legacy Biagio leaves us, along with the purpose of making Palermo an increasingly intercultural and inclusive city. It was like losing a common friend and having all shared together the good he sowed by managing to make us listen to the cry of the invisible.”

This is how Anna Staropoli, sociologist at the “Pedro Arrupe” Institute, commented on the last farewell to Biagio, who was neither a friar nor a priest, but everyone called “brother.”

“It was not a farewell, but a public moment of gratitude,” adds Don Enzo Volpe, a Salesian, former director of the Santa Chiara Center and now involved with ”Casa Ancora.” “An example of strong communion with the poor and a continuous goad for institutions, but more than anything a man touched by Christ.”

The Pauline Bookstore on Corso Vittorio Emanuele is just across the street from the Cathedral, where the funeral was held. “That huge crowd I will never forget. It was a huge emotion because it is the people who moved spontaneously.” Sister Fernanda Di Monte, of the Daughters of St. Paul, has known Brother Biagio for more than 20 years; she also helped director Scimeca with the film released in 2014 that “at first, he was against.”

For the nun, he “was an ‘inconvenient’ sign from Heaven; he repeated to us that the poor should be cared for, with respect, and not assisted. From nothing, it was a crescendo of many works.”

From Brancaccio, Fr. Maurizio Francoforte, from the parish of “San Gaetano,” the one that was Blessed Fr. Pino Puglisi’s. A friendship of more than 15 years, united in ideas and illness. “He succeeded in realizing the dream of a more just human society, without ever becoming discouraged or compromising. He had already envisioned the Citadel on Decollati Street where others saw only the ruins of an abandoned barracks and garbage. Seen from the outside, in fact, he was considered either a saint or a raving lunatic.”

Bishop Bishop Corrado Lorefice also spoke of Biagio’s madness during his homily, calling for “the synod of a new Church, of a new Palermo.”

It is the commitment that falls to everyone from now on in a city that has suddenly found itself an orphan but has the opportunity to become an adult. “I hope Biagio’s death can serve to shake consciences even more and seriously question another kind of society,” Don Pino Vitrano hopes. Far from straw fires, striking gestures and the wave of emotionalism.

“We need to be communicators of good and nurture virtuous circuits,” suggests Serena Termini, Redattore Sociale correspondent, who has followed many of his battles. “Able to leap over superstructures, he believed very much in the power of the word.”

Although often “his voice went unheard,” Father Alessio Geraci, a young Comboni priest from Palermo, points out that “his simple speeches, the fruit of a profound experience of God, knew how to reach the hearts of his listeners and transform them. A prophet who also spoke with gestures and concrete actions, such as fasts, hunger strikes, appeals, pilgrimages. A point of reference for everyone.”

Including young people from Brancaccio’s I care group, such as 20-year-old Alessandro Zangara (“he is a source of inspiration, because he showed us how even with nothing you can give help”); Ida Gagliano (“he taught us true transgression”); Monia Casella (“I met him the day before his death: he had the serene face of one who loved God“); Valentina Casella (”a man who seemed to have come out of the Middle Ages but who, in 2023, drew an entire city to him, to bring it to Christ”).

Now, Brother Biagio rests in the “House of Prayer for All Peoples,” a warehouse on Decollati Street transformed into the church that celebrates dialogue between cultures. From his coffin, made by a deaf-mute Muslim brother from the wood of railroad sleepers, he once again speaks to us of other possibilities and a new life. Because, if you stick around a station, starting again is the most beautiful and sensible thing to do.

An adventurous life in search of God

Born in 1963, the lay missionary died in Palermo on Jan. 12, 2023, at age 59 from colon cancer. At age 26 (1990), he left his wealthy family to seclude himself from the world and walk to Assisi. Tracked down by “Chi l’ha visto?”, he returned to Sicily determined to leave for Africa, but was troubled by the homeless in his city’s train station. He then began his work there and in 1993 founded the Hope and Charity Mission, which was followed by the Women’s Community (2003) and the Citadel of the Poor and Hope (2018), along with other communities scattered around the island. Despite having welcomed until before the pandemic more than 1,000 brothers and sisters (homeless, ex-prisoners, migrants, etc.), Biagio often felt the need to protest, fast, retreat into hermitage, to keep the focus on precariousness and indifference. His last phrases: “I love you”; “Take care of the poor”; “Hold firm the Church.”

(Loredana Brigante, from People and Mission, May 2023, pp. 22-25)

Source

- Popoli e Missione